Maryland's Political Geography in the Early Republic

The Mapping Early American Elections (MEAE) project presents visualizations of the election returns contained in the New Nation Votes (NNV) collection of election returns. These visualizations, presented in the form of maps, afford researchers an ideal opportunity to examine the role of geography in shaping the outcome of the state’s early political contests. Unlike many other states, whose election returns are scattered or incomplete, Maryland has an almost complete set of election data for the period from 1789 to 1824. At the same time, Maryland’s topography and physical features—especially its two major waterways—created a situation in which geography played a determinative role in shaping the state’s political development. While the political history of the early American republic has traditionally been told as a contest between two emerging parties—first, between the Federalist and Anti-Federalists, and later, between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans—Maryland offers a bracing counter-example which complicates this conventional narrative.

At the time of the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, state-level politics in Maryland had already split into two distinct voting blocs. There was a creditor bloc that primarily represented wealthy landowners and planters, who favored higher taxes. These taxes, collected in hard money, were to be used to pay off Maryland’s war debts. Such taxes, however, imposed severe hardships on small farmers, who were suffering from a post-war economic depression and lacked access to hard money. These individuals, who often identified with the debtor bloc, opposed high taxes and wished to pay their taxes in the form of commodities, such as farm produce, rather than in hard cash. While creditors generally supported a strong national government, debtors generally opposed it.

During Maryland’s first congressional election in 1789, these voting blocs coalesced into more formal political alliances. While many from the creditor bloc became affiliated with the Federalists, many from the debtor bloc identified with the Anti-Federalists. In Maryland’s first congressional election, the Federalists made a clean sweep of the offices, with all six of their candidates being elected by a large margin. The Anti-Federalists received a majority of the vote in only two counties, Baltimore and next-door Anne Arundel. With their initial victory, the Federalists seemed poised to dominate Maryland elections for years to come. However, before the second congressional election, an important decision in Congress—the Compromise of 1790—sparked a re-configuration of the voting blocs along geographic lines. This new alignment would shape the state’s politics for the next thirty years.

In the First Congress, two major issues generated intense controversy: the assumption of state war debts from the American Revolution and the location of a new national capital. Numerous locations for the new capital were proposed, including New York City; Germantown, Lancaster, York and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as well as Trenton and Princeton, New Jersey. Many of these cities had previously hosted the federal government during the American Revolution. Of special interest to residents of Maryland was the proposal of two locations on the upper Chesapeake: Baltimore (which briefly hosted a fleeing Continental Congress in 1776) and Annapolis (home to the Confederation Congress for two months in 1783). Nevertheless, it was well-known that President George Washington preferred that the new capital be located on the Potomac River, at a site close to his home at Mount Vernon, Virginia. As it happened, this site also was quite near the demographic center of the country at the time. The Compromise of 1790 resolved both issues at the same time. In the famous “dinner table” bargain, northern states agreed to the the assumption of state debts by the federal government and in return, southern states received a southern location for the new capital.

Reactions in Maryland to Congress’s decision were split along geographic lines. Marylanders living around the Chesapeake Bay were furious with the federal government and with their own representatives who had voted in favor of the Potomac location. Residents of Baltimore and Annapolis believed they had lost a great opportunity for economic growth and prosperity. At the same time, Marylanders who lived near the Potomac River applauded the decision. In addition to placing the county’s permanent capital in their area, Congress had also set up the Potomac Company, a firm that planned to build a canal to transport goods from western regions to east coast port cities. As a result, these areas tended to trust and support the federal government.

This split produced a long-term regional rivalry between the counties in different parts of the state. In the second election for Congress, Maryland political leaders discarded their national party affiliations and embraced new party labels—“Chesapeake” Party and “Potomac” Party—to indicate the importance of local issues, even in an election to national office.

When Marylanders voted in the second congressional election on October 4, 1790, not only did they vote for parties unique to Maryland, but they also engaged in an one-of-a-kind voting procedure. All of the other states at the time (except Delaware) used one of two types of voting methods: the at-large system, in which candidates who resided anywhere in state and received the most votes overall were elected to office, or the district system, in which a state was divided into districts and each district’s voters elected one (or more) persons to represent their area. Maryland’s six representatives were elected using a distinctive variant of the at-large method. While the six candidates with the most votes were elected, voters had to select one candidate who resided in each of state’s six districts.

Conveniently, both the Chesapeake and Potomac parties produced a slate of six candidates, one from each district. The Chesapeake’s ticket included Philip Key (District 1), incumbent Joshua Seney (District 2), William Pinkney (District 3), William Murray (District 5), and Upton Sheredine (District 6). The Potomac Party ticket included James Tilghman (District 2), and incumbents Michael Stone (District 1), Benjamin Contee (District 3), George Gale (District 5), and Daniel Carroll (District 6). Interestingly, both parties named Samuel Sterett from Baltimore as their candidate for District 4. The Potomac Party, it seems, could not find anyone willing to challenge a Chesapeake candidate in the Baltimore area. As a result, Sterett received almost 6,000 more votes than any other candidate.

As a testament to the importance of the issue, Marylanders, especially in the Chesapeake counties, came out to vote in extremely high numbers. Baltimore city itself experienced an astoundingly high voter turnout rate of 99%. Chesapeake voters made their outrage at the Compromise of 1790 known. Consequently, the Chesapeake Party swept the field, emerging victorious in all six of the districts. The five incumbent Potomac candidates, who had generally supported the Potomac location for the capital, were defeated, and the makeup of Maryland’s congressional delegation was significantly altered. The results of this election were so staggering that the state legislature, dominated by Federalists, promptly altered the state’s voting procedures for the next congressional election and switched to a traditional district system.

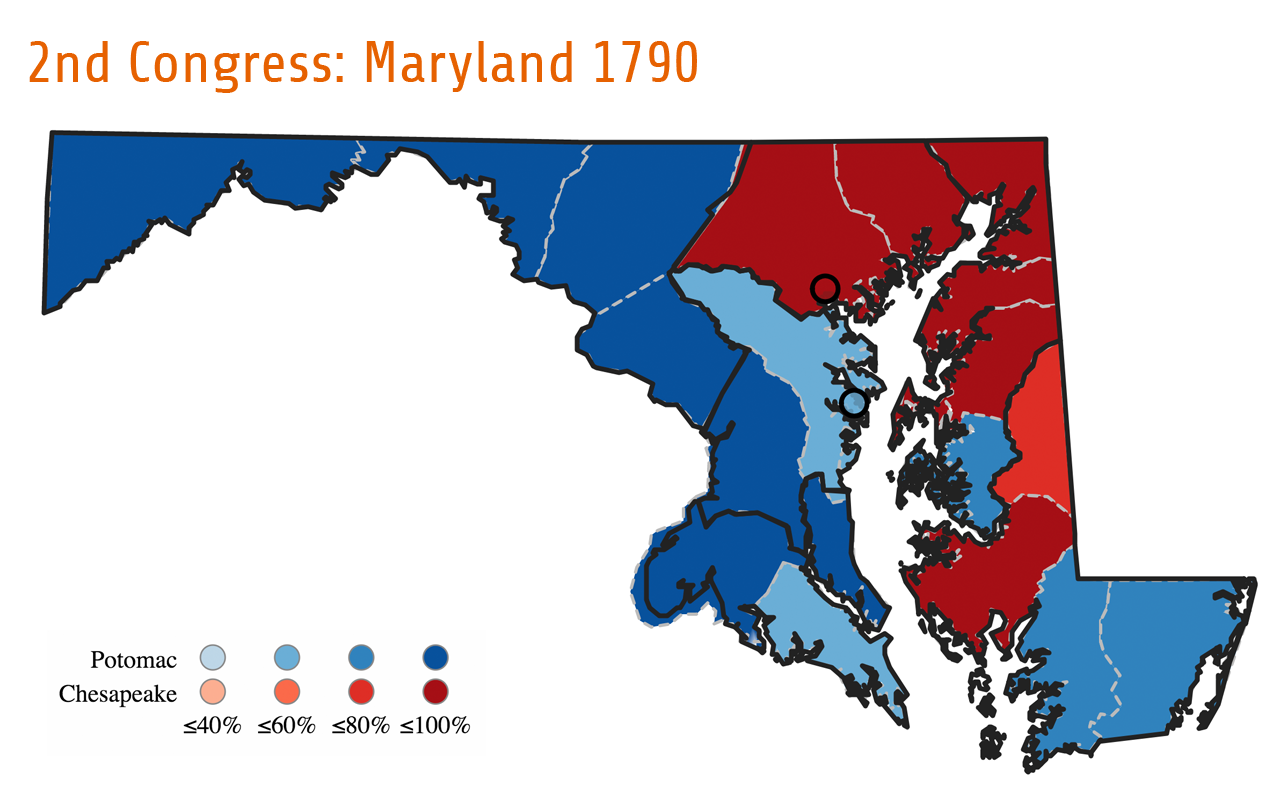

As the map for Maryland’s Second Congressional election (figure 1) shows, the Chesapeake Party’s victory was fueled largely by support in the Upper Bay and Eastern Shore areas (highlighted in red). Voters in Baltimore city and Baltimore County choose Chesapeake candidates almost exclusively (33,189 to 12 votes), and joined with other Upper Bay voters in Harford, Cecil and Kent counties to form a powerful alliance with a large number of voters. In addition, the Chesapeake Party received staunch support from the Eastern Shore, receiving 93.8% of the vote in Queen Anne County, 99.3% in Dorchester, and 67.6% in Caroline. In contrast, support for the Potomac party (highlighted in blue) followed along the Potomac River and included Allegheny, Washington, Frederick, Montgomery, Prince George’s, Charles, and St. Mary’s counties. Interestingly, the Potomac party also received support from some counties not directly on the river, such as Calvert, Talbot, Somerset and Worcester counties. Finally, in areas located between the Potomac and Chesapeake regions, votes were almost evenly split. For example, in Ann Arundel County, the results were 48.3% for the Chesapeake party to 51.7% for the Potomac party. In Annapolis, 49.1% of the voters supported the Chesapeake party while 50.9% voted for the Potomac party.

Despite the formation of these two cohesive, regionally-based voting blocs, the Potomac and Chesapeake parties appear as clearly identified parties only in this single election. Two years later, candidates running for the the third Congress identified themselves as “Federalists” and “Anti-Federalists,” signaling a return to national party affiliations. However, while the “Potomac” and “Chesapeake” party labels disappeared, the general regional alignment established during the second congressional election remained. Although the regional voting blocs were never as tight-knit as they had been in the 1790 election, they continued to influence voting patterns throughout the state for almost two decades.

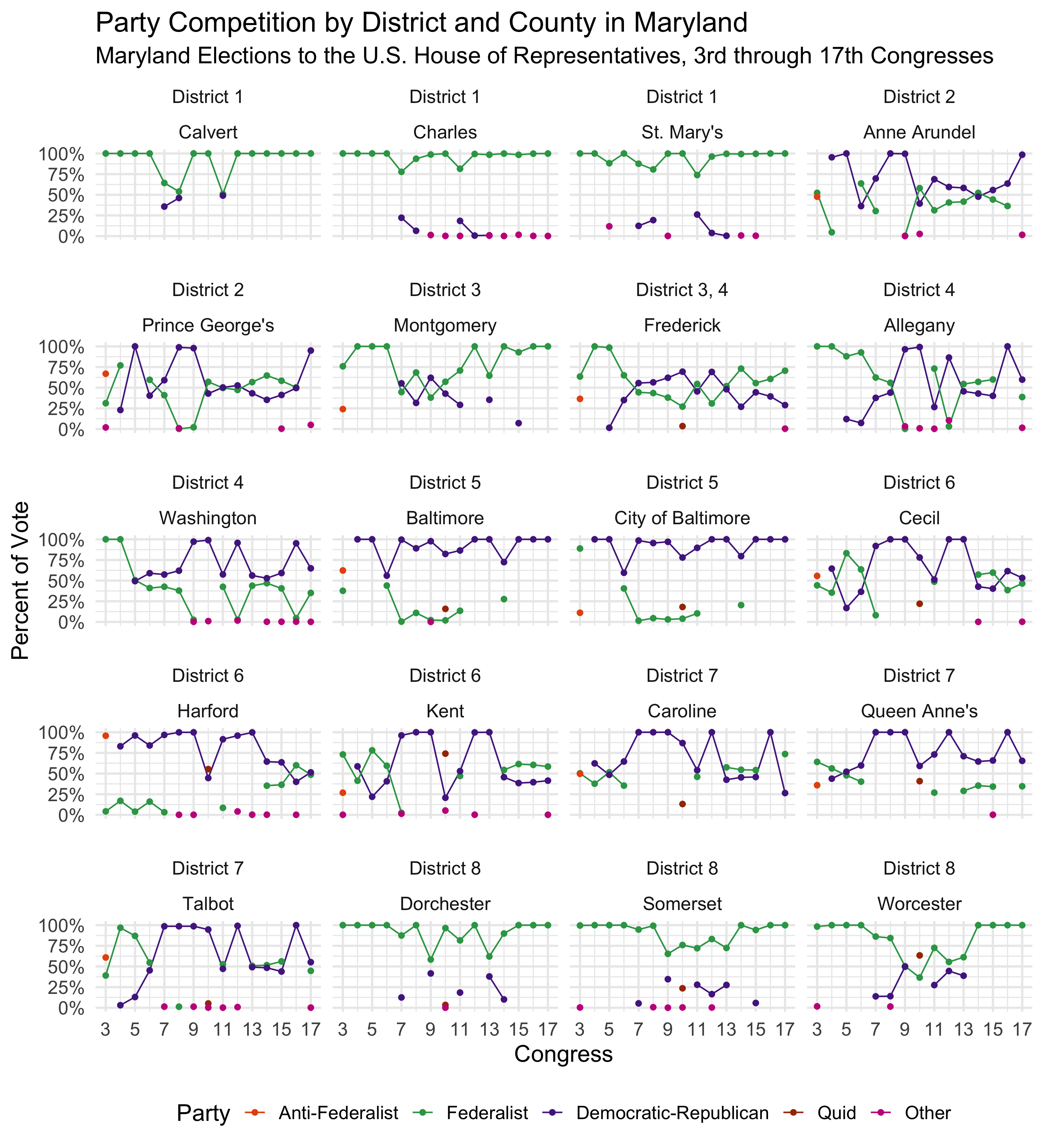

The continuation of these regional divisions can be seen in the maps and charts depicting Maryland’s third through seventeenth Congressional elections (figures 2 and 3). From 1792-1820, distinct voting patterns emerged in three geographical areas: consistent support for the Democratic-Republicans in the Upper Chesapeake (Districts 5, 6, and 7), in places which had supported the Chesapeake party; consistent support for the Federalists in southern Maryland (Districts 1 and 8), from areas that had supported the Potomac party; and consistently mixed voting patterns in Maryland’s western and middle areas (Districts 2, 3, and 4).

The voting patterns of these three regions continued into the 1820s. However, the 1824 presidential election altered these long-entrenched geographically-based trends. As in many places throughout the country, candidates in Maryland came to identify less as Federalists or Republicans, and instead became associated with their choice of presidential candidate: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay or William Crawford. The geographical alliances and local issues that had dictated Maryland politics for over thirty years had collapsed. National issues and national personalities finally overrode locally entrenched concerns.

Throughout the first years of the new nation’s existence, geographic considerations and local issues often played a significant role in determining party allegiances and political preferences. While most other states did not demonstrate the extreme localism evident in Maryland’s congressional elections, many others did have geographically based partisan allegiances. At the same time, Maryland’s early political development also reflects the larger pattern of party evolution that appeared in other states—a pattern in which politics was tumultuous at first, with shifting party labels and alliances, but eventually yielded to more consistent voting patterns and stable party affiliations. Yet by the 1820s, this pattern, in Maryland and elsewhere, was disrupted by the the splintering of the Democratic-Republicans and the eventual decline of the Federalists. In fact, Federalists in Maryland persisted as a force in state politics much longer than in many other places. Nonetheless, by the mid-1820s, new party configurations were already on the horizon.