Electing Members of Congress in the Early Republic

District vs. At-Large Elections

Until 1825, the U.S. government did not require that local election officials formally report the results of their contests to any state or federal officials. Without official sources of election returns, research into the development of early American electoral politics has been severely hampered, or based on fragmentary data. Yet returns for local, state, and federal elections have been found in a variety of other sources, including, newspapers, state archives, local repositories, and private archives. Drawing together the results of years of research, the New Nation Votes (NNV) database reports the raw data for over 60,000 local, state, and federal elections for the period before 1825, and is the most comprehensive set of election returns for the early national era available.

The Mapping Early American Elections (MEAE) project builds on the election results reported in the NNV transcriptions of elections returns. Although town, county, and district-level information may be available in the NNV, the MEAE website maps only county-level results. An original dataset has been created that regularizes the election results as well as accounts for the kind of historical variation in election laws and procedures in each state that will be described below. This approach allows for comparison of the results over time and across states.

Procedures for electing members of Congress in the early republic greatly differed from the single-district system that is in use today. During the American Revolution, Americans began to institutionalize the meaning of self-government by writing their own state constitutions, beginning in 1776. In subsequent decades, some states re-wrote their constitutions. New states, as a condition of their admittance to the Union, also produced state constitutions. These documents, which varied widely, described how each particular state would govern itself, prescribing everything from voting requirements, to the composition of the state legislature, to the way in which its legislatures would be elected.

The U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1789, gave the states another task: to determine “the Times, Places and Manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives” (Article 1, Section 4). Each state legislature thus had the responsibility to define the specific procedures by which the state’s legislators would elect its Senators, and the people (i.e., eligible white male voters) would elect the members of its congressional delegation. Each state also had the authority to prescribe the requirements for voting and the days and times when federal elections would be held. If the state chose to elect its members of Congress using a district system, the state’s legislators would also draw the boundaries that determined the extent and shape of congressional election districts.

For the first several decades of the new nation’s existence there was no uniformity in how—or when—the states within the United States elected their members to Congress. States held elections at various times from March through November of the year preceding the opening of a new session of Congress. There was a wide variation from state to state. Election procedures also varied and changed over time. Mapping the results of congressional elections thus requires knowledge of a state’s election laws at the time of a particular election. This information is embedded in the maps that are presented in the MEAE website.

In deciding how to elect their members to the U.S. House of Representatives, state legislatures used the geographic units typical for their region as the basis for their efforts. In New England, towns were the main political unit, and voting took place in their meetinghouses, churches, or town halls. In the Middle Atlantic States, although voters cast their ballots in towns, the county was the main political unit. Election returns were reported at the county level. Local newspapers sometimes gave the results from individual townships. Among the original southern States, the county was the main political unit. Voting often took place at the county court house, and for those counties with large populations, also in taverns, churches and general stores.

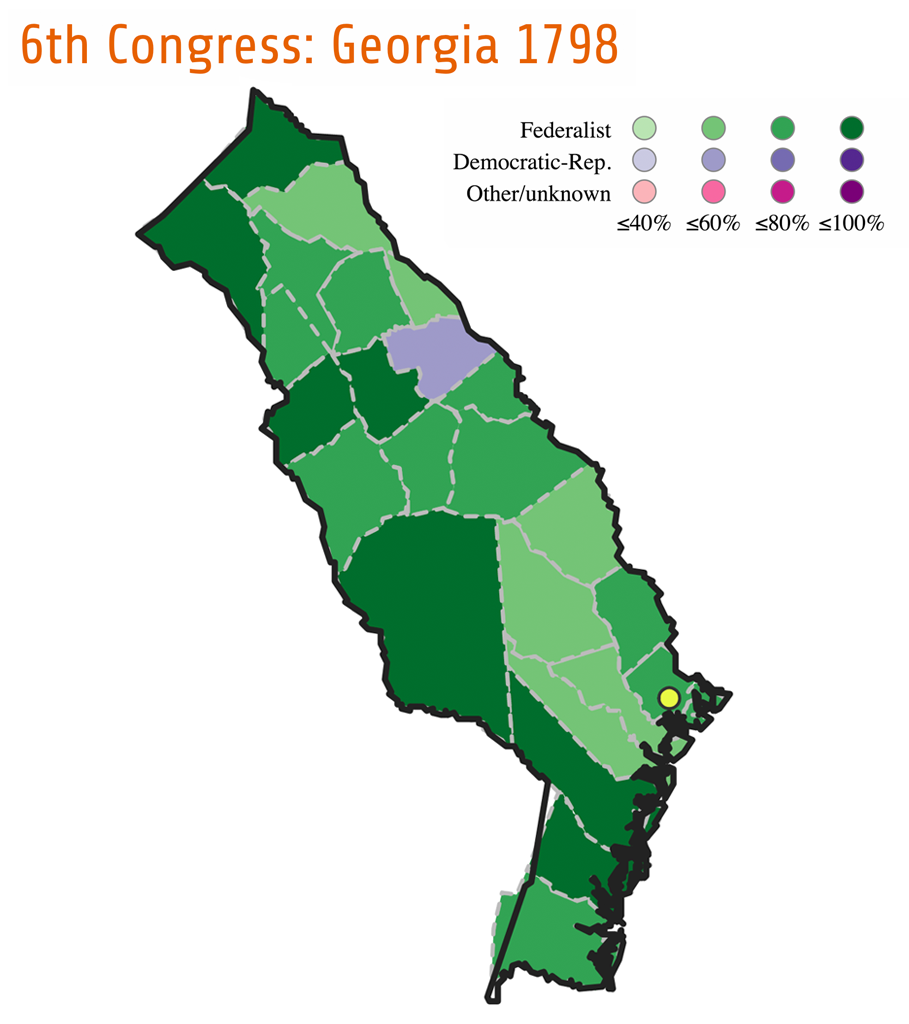

The variation in election laws produced a variety of methods for electing members of Congress. The most common method of electing candidates was the At-Large system, in which each voter cast one vote for two or more candidates. Voters in Georgia, which used an At-Large system, cast a single ballot, which included the names of several candidates. For example, in Georgia’s sixth congressional election (figure 1), voters cast one ballot, but wrote in two names. At least six states used the At-Large method exclusively to elect their Congressmen from 1792–1824. A few others alternated from single member districts to At-Large, mostly when one party or the other thought that the At-Large method would give an advantage to their side.

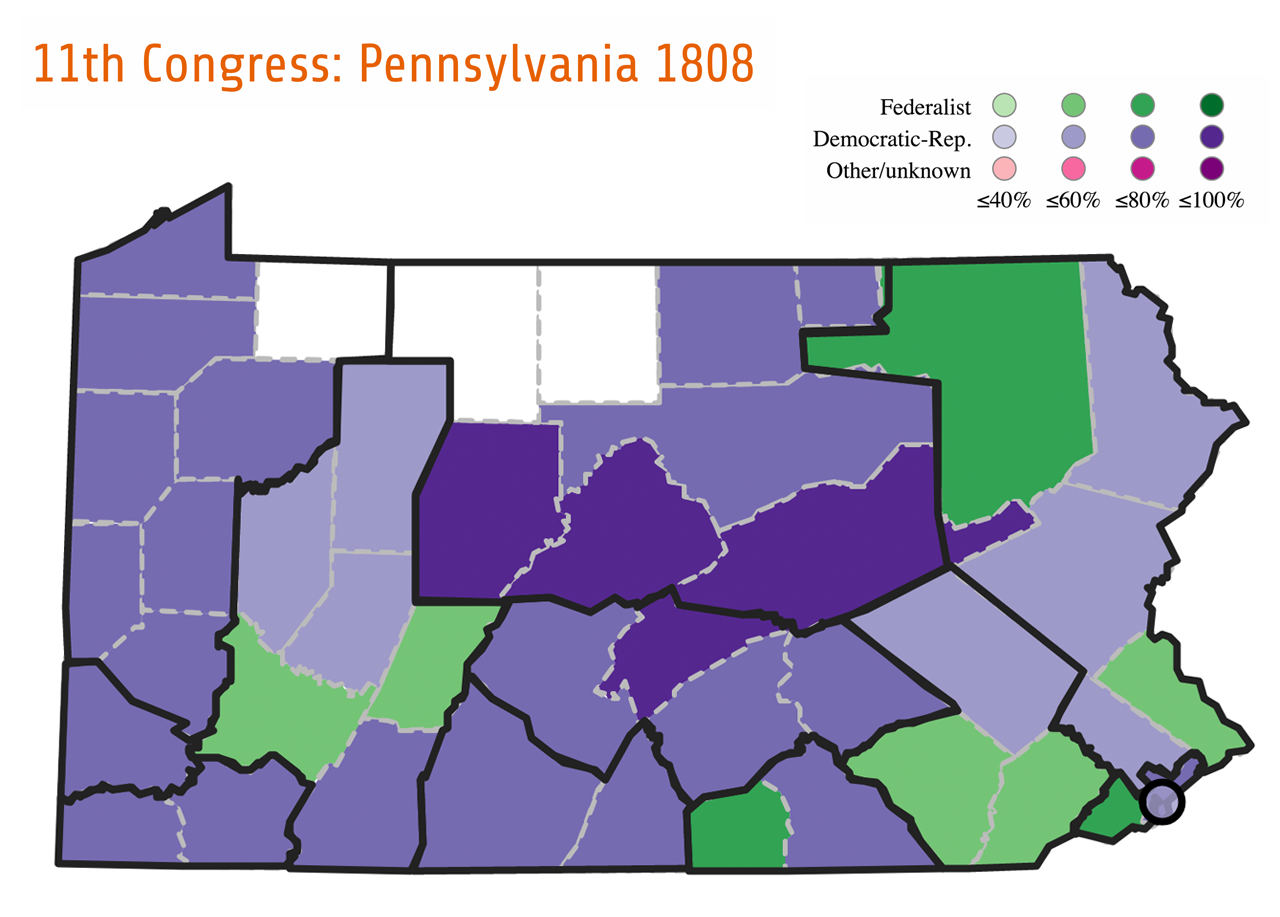

Although single member districts were by far the most common, a few states created what were called multi-member districts. These were districts that elected more than one candidate. Pennsylvania, the first to use this method, had four of these multi-membered districts from 1802–1810, electing eleven congressmen, and from 1812–1824 there were six, electing fourteen representatives. Most of these districts had one, sometimes two Federalist-leaning counties, which could by themselves, have been separate districts. Based on how these counties were grouped together, evidence suggests these multi-membered districts were created mainly for political reasons.

New York started using this method in 1804, establishing one multi-member district. This increased to six multi-members districts between 1812–1820, which elected twelve congressmen, and then tapered off to three multi-member districts in 1822, which elected seven representatives. The motivation in forming these districts does not appear to be political. At least two of them were constructed to avoid breaking up New York City, and others in anticipation of the rapidly growing western counties. Multi-member districts were used until 1842. It should be noted that state legislators were reluctant to split existing counties up when they were making districts. By the early 1820s, as more and more counties were organized and population shifted westward, it became necessary to separate towns from their original counties and assign them to surrounding districts. During the 1810–1820 period, both New York and Pennsylvania started to engage in this practice.

In certain states, if no candidate received the required majority, additional elections were held (called trials or run-offs) until someone received the required majority. This was especially true in New England. Before the two parties became fully organized, there were often numerous additional trials and run-offs, particularly in Massachusetts and the part of Massachusetts that eventually became Maine. In other regions, however, a mere plurality of votes was sufficient.

The wide variation in methods of electing members of Congress produced a number of useful and creative electoral procedures. These methods reflected an ongoing debate about the nature of representation in the new republic. Over time, however, many political leaders began to recognize the need for greater uniformity in electoral practices. In the 1842 Reapportionment Act, Congress passed a law requiring that states use the single-district system in electing their members to the House of Representatives. Nonetheless, a small number of states ignored the law and continued to use the at-large method or employed multiple-member districts. Only in 1967 would the mandate for electing congressmen through the single-district method be both universally required and enforced. In addition to restricting how members were elected, Congress also began to control when members were elected. On February 2, 1872, a law was passed decreeing that elections for members of Congress as well as for presidential electors would occur on the same day, the first Tuesday in November. The era of experimentation had come to an end, and with it, the states’ unrestricted authority over the time, place, and manner of electing members to Congress.