Geolocating the Towns from A New Nation Votes

August 22, 2017What do the towns of Middle Hero, Vermont, Castleton, New York, and Enfield, Massachusetts have in common? They all have voting returns in the New Nation Votes dataset (NNV) and they don’t exist anymore.

NNV contains voting returns at the town, county, and Congressional district level. This geographic information is limited to general place names only (e.g., the town of Suffrage, Otsego County, the tenth Congressional district in New York). Before these locations can be mapped, additional spatial data is needed, such as the latitudes and longitudes of towns or the historic boundaries of counties. Fortunately, there are several spatial datasets that already exist (referenced on our data page) that can be joined to NNV through unique identifiers that we have created. For both the county and Congressional districts, this spatial dataset is sufficient and provides the needed geographic data to map them.

The NNV towns list, however, has required additional work to properly geolocate.

First, the NNV towns’ data needed to be standardized and consolidated. As we noted in an earlier blog post on the differences between the Mapping Early American Elections project and the New Nation Votes project, NNV is a transcription of election returns found in various sources, not a ready-for-mapping dataset. Variation in spelling, changing town names, and even multiple distinct towns with identical or nearly identical names are all issues within the NNV transcriptions. If left unresolved, these discrepancies lead to errors in mapping and interpreting the data. Election returns could be assigned to the wrong town or spread among numerous spellings of the same town.

Rooting out these issues can be complicated.

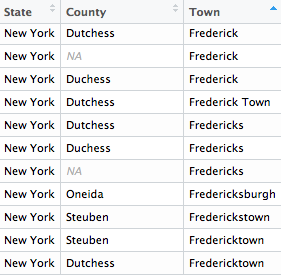

Let’s use the town of Fredericks, New York as an example. It was formed out of a section of Frederickstown in 1795. It remained under the name Fredericks until a legislative act changed the town name to Kent in April of 1817, which remains the town name to this day. Additionally, the county boundaries changed during the period of the NNV returns, with the result that Fredericks/Kent moved from Dutchess to Putnam County. Thus, each of the “Frederick,” “Fredericks,” “Frederick Town,” and “Kent” should be consolidated into a single town. Different listings for Frederickstown/Fredericktown in Stueben County actually refer to a town distinct from Fredericks/Kent. This town was further west in the state of New York, and its name was changed to Wayne in April of 1808.

Locating this information about changing place names required examining various county histories. The United States Geological Survey also maintains the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) which is a database containing the naming information for numerous “physical and cultural geographic features of all types in the United States.” The process of standardizing the towns involved creating a CSV containing each of the NNV towns (with all of their variations) and a list of the standardized, distinct town names. With this data table, I could assign unique identifiers to each of the distinct towns making future data analysis much easier.

With the NNV towns standardized and checked for historical accuracy, we then moved on to the two-step process of geolocation. First, we passed a CSV of the unique towns (combined with their county and state) into a Google API for geolocation, which returns a latitude and longitude for each town it locates in its database. It also returns other administrative information that can be useful in verifying the town’s location.

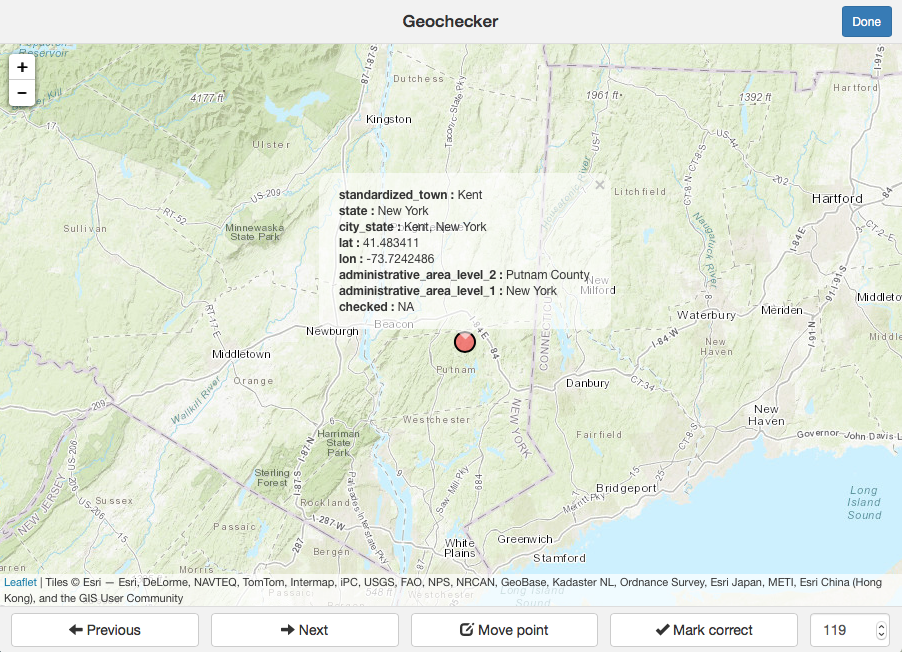

The second step in geolocating the towns involved checking the accuracy of the Google results. To help with this, we created an app called Geochecker to provide a tool for easily verifying geocoded locations.

The Geochecker app mapped each of the towns listed in the NNV onto a contemporary basemap. Each point has a pop-up window that displays the relevant information from the data table. Going through the data table one by one, I checked the accuracy of each town’s latitude and longitude using Google Maps, the ESRI basemaps (as shown in the Geochecker tool), and David Rumsey’s collection of historical maps. Additionally, the county histories provided contextual information that also aided in locating the various towns. Finally, the Geochecker app creates a new variable column in the data table designated as “checked” that records when a town has been marked correct. This left a record for me as I would take a number of days to get through a single state’s town list. In the end, the process created a CSV of the standardized, distinct towns and their latitude and longitudes, as well as a CSV of the NNV towns and standardized towns.

An important secondary result of geolocating towns was the gathering of local and town histories. In line with RRCHNM’s goal to democratize history, and wanting to share the wealth of information I was reading, I devoted time to updating various town Wikipedia pages. Most towns have their own Wikipedia pages detailing the history, demographics, climate, notable individuals, etc. and would often be lacking in proper citations. Adding to or correcting the town histories and citing the county histories from which the information came, is a useful side benefit of the Mapping Early American Elections project.