What Did Democracy Look Like? Voting in Early America

September 1, 2017Early American elections subvert conventional notions that portray the development of early American democracy as an orderly or systematic affair. In contrast to the well-organized procedures governing voting procedures today, elections during the first few decades of the new nation’s existence were often haphazard affairs. Everything from the location of the polls to the qualifications of the electors to the number of days the polls would be open varied from state to state, and often, from election to election. Sometimes going to polls could be injurious to one’s health, since they were occasionally the scene of riots. Democracy, then, evolved less by design and more from a constant push-and-pull between those seeking to cast their ballots and those who made the rules about when, where, and how the ballots were to be cast.

Article I, Section 4 of the US Constitution gave state legislatures the power to determine “the Times, Places and Manner” of federal elections, along with the power they already possessed to determine rules for state elections. Suffrage requirement for the lower houses of their legislatures also determined requirements for the federal franchise. As a result, the variation in election rules and procedures makes the task of generalization very difficult—and made the process of running the newly established federal government even more challenging.

There was, for example, no uniformly established day on which to hold elections. In New England and New York, for example, elections tended to occur in the spring for legislative gatherings that would convene later in the year. In the Mid-Atlantic states and Upper South elections were often held in the late summer or the early fall. South Carolina and Georgia preferred late fall elections, although they were soon moved to October to accommodate Congress’s schedule.

Before the election, candidates tried to meet potential voters and get their name into circulation. At this time, however, they seldom made formal speeches or directly solicited votes. Instead, they might make their views known through letters to the local newspaper or rely on friends and allies to celebrate their patriotic virtues and sterling leadership qualities. At least until the second decade of the nineteenth century, “electioneering,” as it was called, was disdained. Candidates did, however, have other ways of persuading their potential constituents. Although officially prohibited, the custom of “treating,” especially prevalent in the South, meant that in the days prior to the election candidates might invite voters to picnics featuring generous servings of barbecue, washed down by copious amounts of liquor. Prior to the 1758 election for the Virginia House of Burgesses, George Washington reportedly served over 160 gallons of rum punch, wine, beer, and other spirits to potential voters. Perhaps not surprisingly, the young Washington triumphed over his opponent.

Whenever they occurred, elections did not necessarily take place over the course of a single day. The sheriff, or other local election official, could if he so wished either extend or shorten the amount of time in which the polls were open. If, for example, excessive rains and flooding made it difficult for voters from an outlying area to reach the polling site, the clerk might keep the poll open for two-to-three days—or in some cases, even a week, so that anyone who wanted to vote might do so. A corrupt official, on the other hand, might choose to prematurely close the polls to prevent certain voters from reaching the site in time.

Elections were communal affairs, sometimes with celebratory overtones, sometimes with more ominous overtones. Elections could be held at almost any public venue—from a town hall to a courthouse to a church or tavern. Arriving at the site, electors often confronted a “tumultuous assemblage of men,” as Richard Henry Lee put it, where people milled about—talking, arguing, and sometimes, drinking. In the North, where elections were more sober affairs, women and children might be present, bringing with them “election cakes,” baked especially for the occasion.

Actually casting the ballot was a kind of public performance. By 1800, most states, with the exception of Virginia and Kentucky, had moved from oral voting (viva voce) to the secret, written ballot. Nonetheless, electors often found themselves at the center of public attention. When they cast their ballots, voters moved one-by-one to the front of a line, under the close scrutiny of other members of the community. They sometimes had to mount a number of steps to reach an elevated dais. There they would place their folded ballot in a slot in a wooden ballot box. Many individuals, including their creditors, patrons, or other powerful individuals, looked on as they did so.

During the colonial period, most colonies, like Great Britain, had required that electors possess property—typically either a fifty-acre freehold or land worth fifty shillings. Although voting qualifications varied from state-to-state, by 1800 a majority of states had lowered, or even dropped, property requirements for voting. Throughout the country, perhaps 80% of all adult white males were eligible to vote. In New Jersey from 1776 to 1807, women were actually allowed to vote on the same terms as men. Only three states—Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia—explicitly confined the vote to white males. There were no voter registration rolls. Electors simply declared that they had met the suffrage requirements for that state. If someone doubted the voter’s eligibility, they would declare their objections to the officials. The individual’s ballot would be set aside, for further investigation. Though not overt, then, the pressure to vote for a certain candidate was often unmistakable.

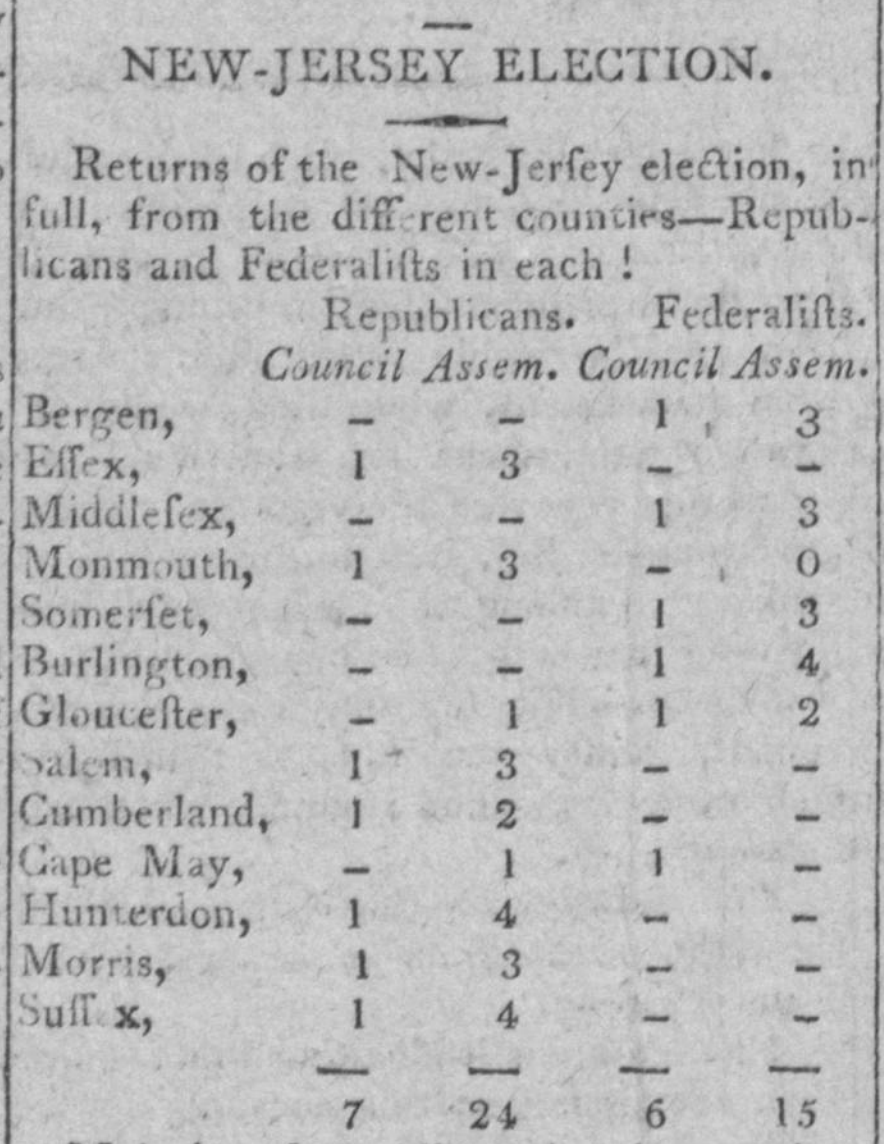

As party hostilities between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans intensified, tensions between participants sometimes erupted into public violence—what was called an “election riot.” It was not uncommon for partisans on both sides to march in formation to the polling site, dressed in their militia uniforms. Bearing guns or sticks, their intention was not only to display party solidarity but to intimidate voters holding opposing views. In 1793, the House Committee of Elections heard testimony about a disputed election in which one candidate’s supporters threatened “to beat any person who voted for [their opponent]”—who subsequently lost. Although no one challenged the veracity of the accusation, the House rejected the aggrieved candidate’s petition. “Why,” said one Congressman, “should there be such a noise about this election in particular, when others were just as bad, or a great deal worse[?]”

There was, then, no uniform or overt march toward democracy in the early United States. The diversity in electoral practices among the states meant that the country remained an experiment in republican government. Within each state, various factions battled with one another to try and work out what its own citizens meant by the march toward democracy.