Political Parties in the Early Republic

The Mapping Early American Elections (MEAE) website is a valuable resource for visualizing the development of party politics in the early United States. This information, however, must be interpreted within the context of the times. Political parties during the early national era were fundamentally different from political parties today, and significantly different even from the parties that developed later in the nineteenth century.

The framers of the federal Constitution had not anticipated the development of permanent political parties. Parties were considered “factions,” dangerous and illegitimate alliances that pursued their own self-interest at the expense of the common good. National leaders were expected to serve the interests of the entire nation, not to cater to any particular regional, class, or state interests. This ideal of governance was first challenged during the debate over the ratification of the Constitution. Opponents of the Constitution, called “Anti-Federalists,” challenged supporters of the Constitution, called “Federalists,” for votes. Despite the intensity of the conflict, these coalitions were transient and disappeared soon after the new government went into operation.

During the first years of the new republic’s existence, two distinct and mutually antagonistic coalitions quickly emerged, coalescing into the first nascent political parties. Historians have come to call these two groups the “Federalists” and the “Democratic-Republicans.” (Note that despite having the same name, the Federalists of the 1790s represented a very different coalition from the Federalists of the ratification period. Similarly, although “Democratic-Republicans” during this era were sometimes simply called “Republicans,” they were not related to the Republican party that formed in 1854 and which continues to the present.)

This was a period of great experimentation and change in the development of political parties. In general, Federalists and Democratic-Republicans espoused competing, and often contradictory, visions of the nation’s future. Federalists, for example, tended to favor a strong central government, a capitalist financial system, and a pro-British foreign policy. In contrast, Democratic-Republicans insisted on the primacy of state governments, an agrarian economy dominated by small farmers (and, in the South, slaveowners), and a pro-French foreign policy. Each side also advocated contrasting visions of society. While the Federalists emphasized the traditional values of hierarchy, stability, and order, the Democratic-Republicans promoted a more egalitarian vision that encouraged an expansion of political realm—albeit only for white males and at the exclusion of white women and African Americans.

In very general terms, during the period before the War of 1812, Federalists tended to dominate in the New England states and Democratic-Republicans were increasingly prominent in the Mid-Atlantic, Southern, and new western states. In Congress, representatives quickly began to identify with one group or the other; by 1793, they began voting as two distinctive blocs. Outside Congress, both parties soon became skilled at mobilizing popular support for their candidates and policies. They founded partisan newspapers, held political parades and public celebrations, and designed new kinds of electioneering techniques to bring out the vote at election time.

Yet these early political parties lacked many of the features of modern political parties. Neither the Federalists nor the Democratic-Republicans had a highly centralized political organization, elaborate election procedures, or a uniform national ideology. State or local issues, rather than national issues, often provided the basis for party affiliation and identification. Most importantly, neither side recognized the other as legitimate. Each party insisted that only its views reflected the true legacy of the American Revolution. Their goal was not to seek compromise with the other party but pursue its extinction.

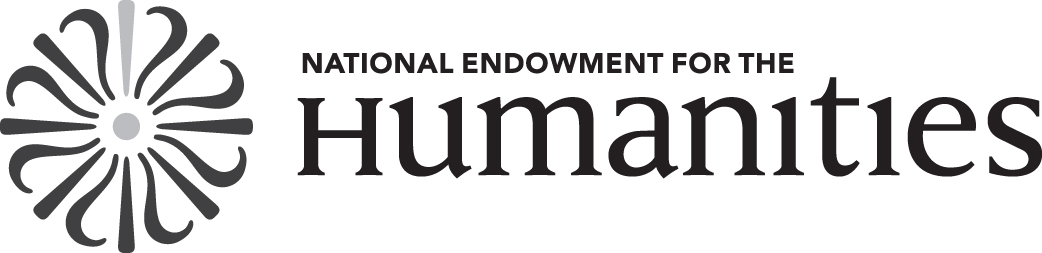

Maps from the MEAE website help tell the stories of these early political parties. In the early congresses, for example, it was not uncommon for party allegiances to shift rapidly and frequently. Between 1798 and 1806, Federalists virtually disappeared in North Carolina—and then staged something of a comeback during the War of 1812 (figure 1). The names of the parties often changed over time or varied from state-to-state. In Maryland, for example, congressional elections for the First Congress revisited the debate over the Constitution and pitted the Federalists against the Anti-Federalists. In 1790, however, candidates from the so-called “Potomac” party challenged those from the “Chesapeake” party in a match that highlighted local rather than national divisions and interests.

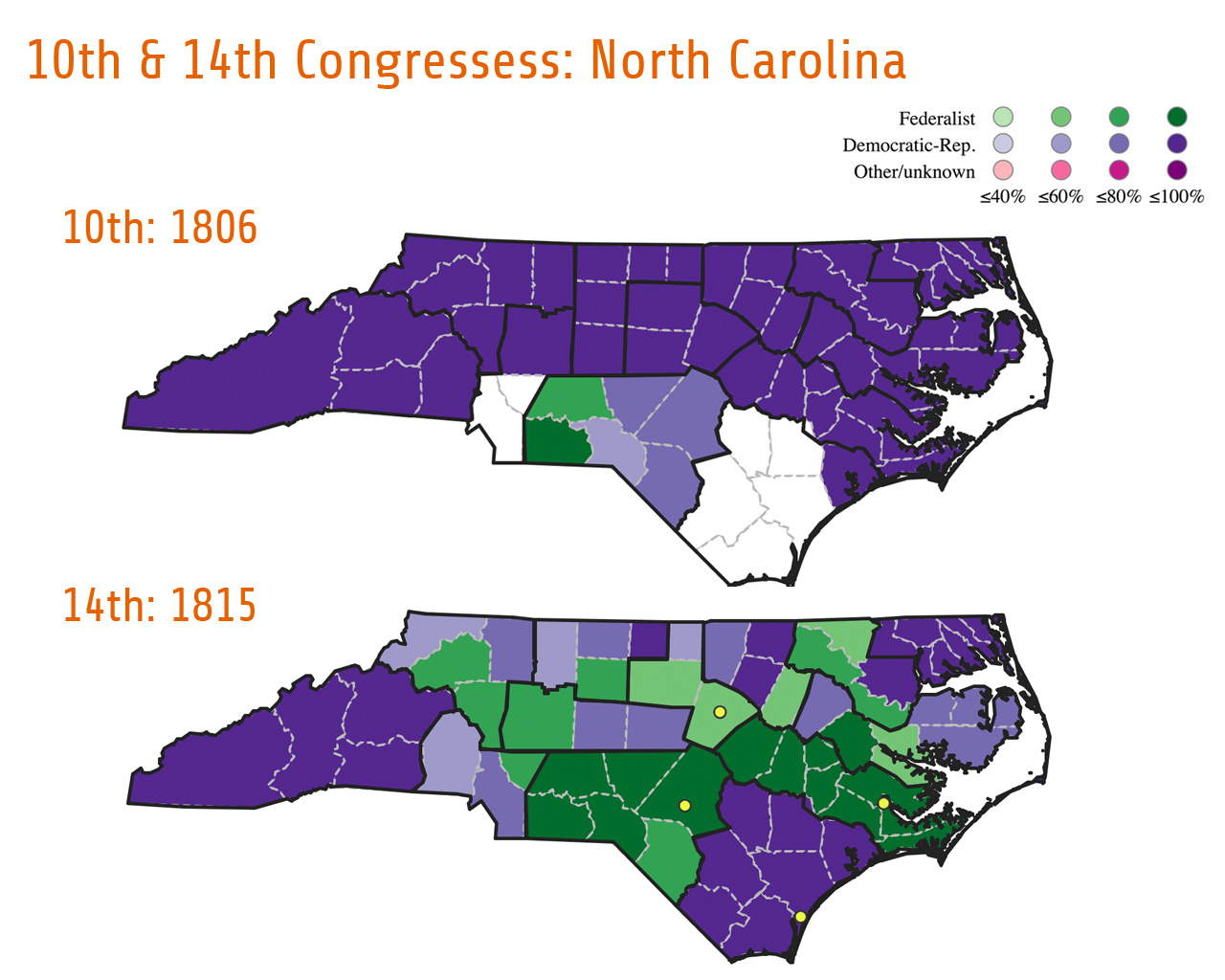

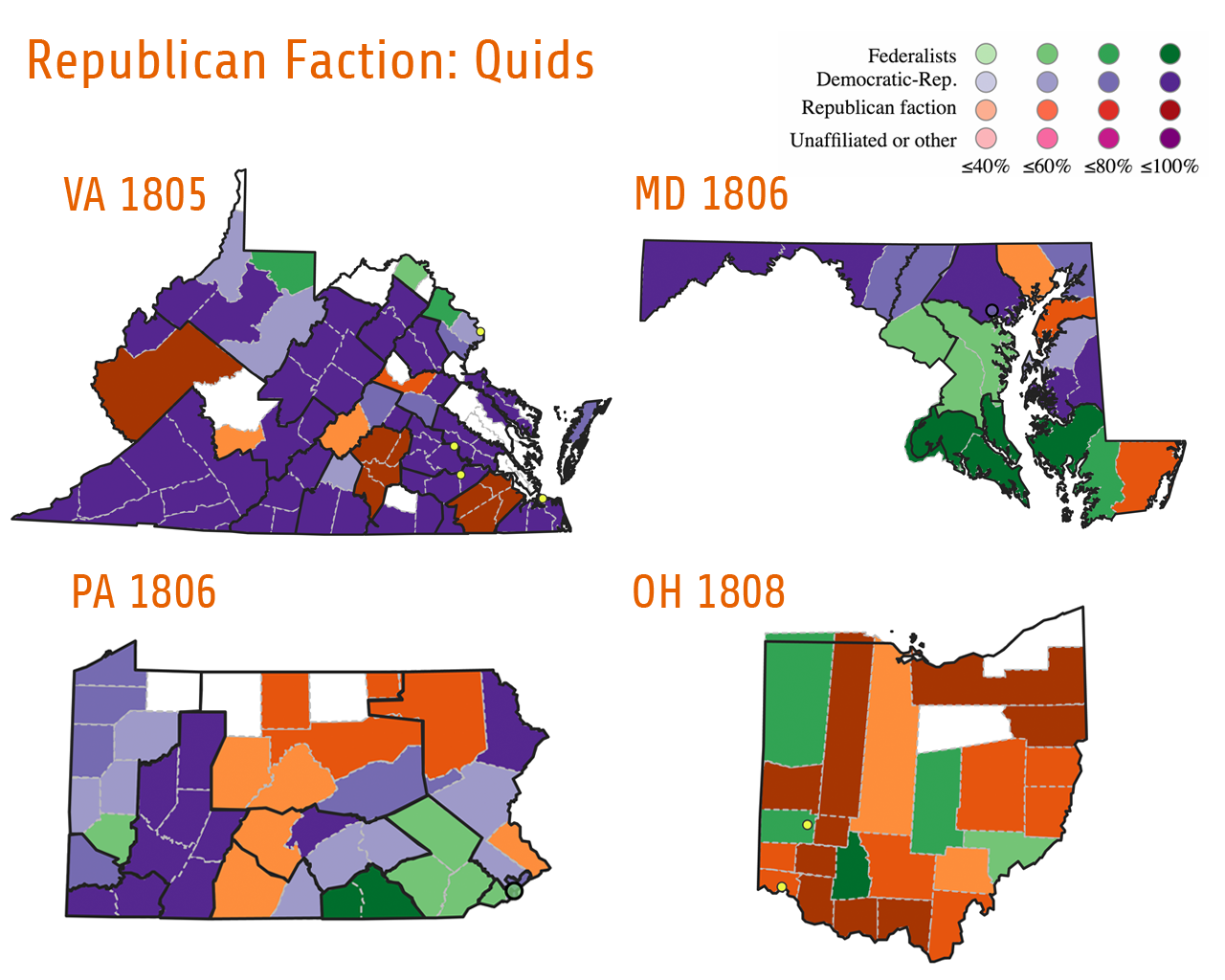

Splinter factions also emerged, mostly among the Democratic-Republicans, that divided the party and created new kinds of alliances. For simplicity’s sake, the MEAE project has identified these splinter factions, from whatever period or state, under the general heading of “Republican Faction.” For example, a dissident Democratic-Republican group called the “Tertium Quids” combined disaffected Republicans with like-minded Federalists. These partisans were especially active in New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and Ohio from 1804 to 1808 (figure 2), before they were re-absorbed into the Democratic-Republican party. New York was in a category of its own, nurturing a huge array of splinter groups. New York included factions such as the Bucktails, Clintonians, Lewisites, Opposition Republicans, and the aptly named Division versus Anti-Division factions (figure 3). Such party designations had local significance but not national recognition. Nonetheless, elected members from these groups usually voted with the Democratic-Republicans in Congress.

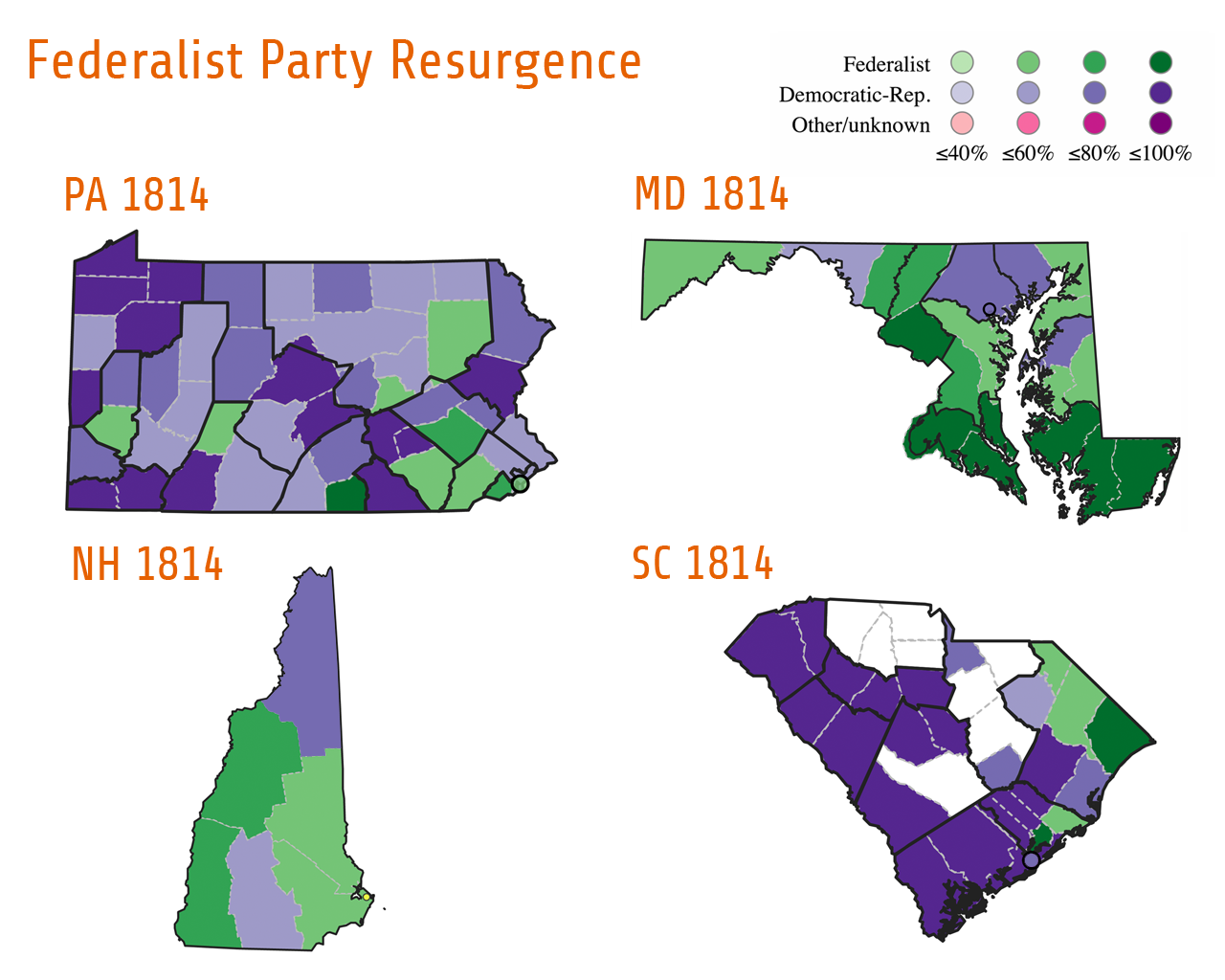

Beginning with the Election of 1800, the Federalists went into a long period of decline. Although they remained competitive in many state and local elections, they lost the ability to win the presidency or control Congress. Nonetheless, the Federalists experienced an impressive resurgence during the Embargo of 1807–1808 as well as the War of 1812. In these periods, Federalist candidates contested many state-level elections and recaptured a number of seats in Congress (figure 4). These developments occurred not only in Federalist-leaning states in New England, such Massachusetts and New Hampshire, but also in Pennsylvania and Maryland. Even South Carolina saw a brief resurgence of Federalist victories.

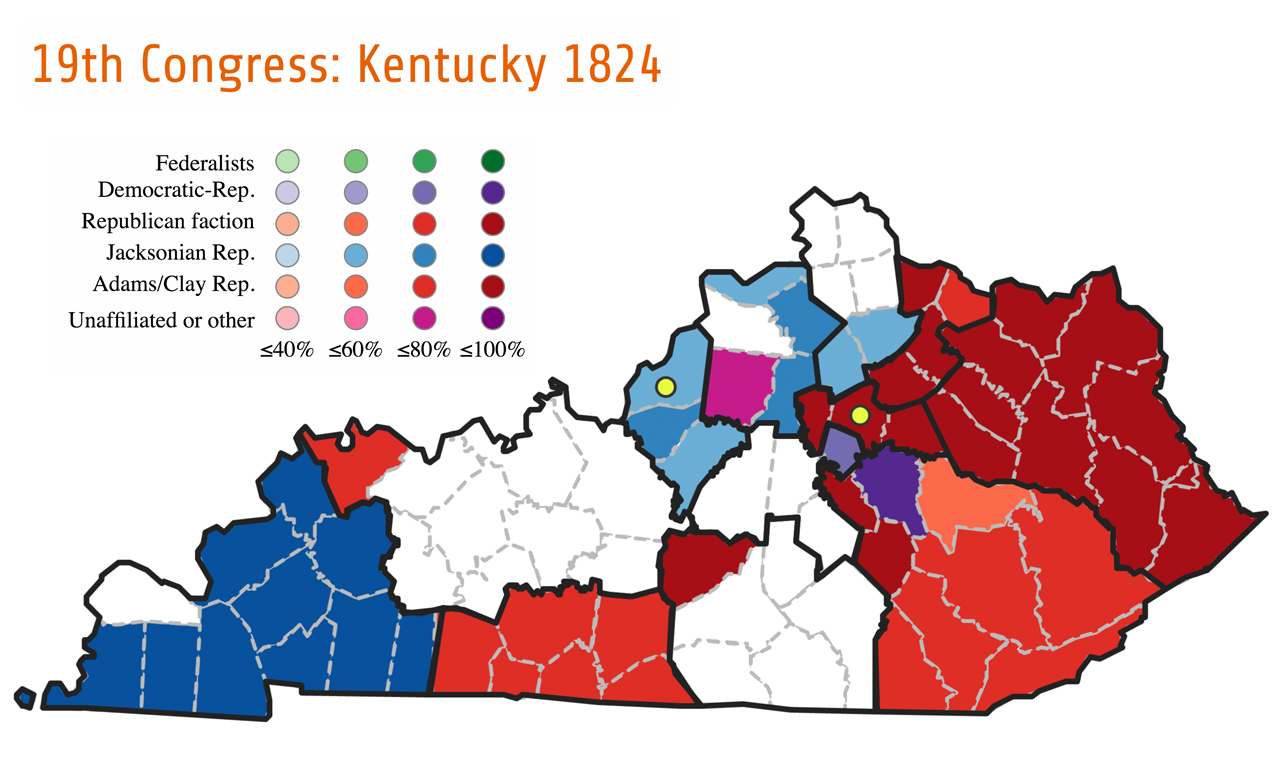

Yet the Federalist victories did not continue. By 1820, the First Party System, featuring the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, had collapsed. A plethora of new parties began to emerge. In the critical election of 1824, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, and William H. Crawford all ran for president, each claiming to represent a different constituency within the Democratic-Republican party. Also in 1824, certain candidates for Congress revealed their political views by associating themselves with (or opposing) one of the presidential contenders. In Kentucky, for example, candidates aligned themselves with either the Jacksonian, Adams/Clay, or traditional Democratic-Republican wings of the party (figure 5). These developments set the stage for the subsequent emergence of the so-called “Second Party System”—a new configuration which pit Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party against Henry Clay’s Whigs during the 1830s.

Convoluted though these developments may be, tracking electoral shifts in early American political parties reveals larger changes in popular political allegiances, partisan ideologies, and sectional tensions. Though limited to white males, these changes demonstrate the growth of what historian Andrew Robertson has called “the tortuous trajectory of American democracy.” Yet it is critical to understand these changes in the same terms that people living in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries understood them. Parties at this time were evolving institutions whose legitimacy and structure were not well-defined—yet which, at the same time, came to occupy a crucial, and unexpected, role in the American political process. Political parties acted as one of the most significant vehicles for linking Americans in their local communities with their far-off and distant federal government. Neither anticipated nor initially welcomed, political parties quickly proved to be an essential feature of American political life.